Published by Frank Penny

22 Oct, 2025

When the studio mixing desk became an instrument.

Let’s go back to Kingston, Jamaica in the early 1970s. The island’s music scene was exploding and reggae artists were beginning to churn out records as fast as the Fans and Selectas’ could consume it, but in the studios after hours the engineers and producers were starting to experiment. They were playing around with popular finished reggae tracks and stripping them back, adding effects and transforming them into something entirely new. They started to become musicians themselves and were treating the mixing board like a musical instrument, riding the faders, dropping out entire sections, and letting the bass and drums breathe in ways no one had heard before.

This was the birth of dub music, and it didn’t just revolutionise reggae, it laid the groundwork for remix culture as we know it today and even helped spark the birth of hip-hop thousands of miles away in the Bronx.

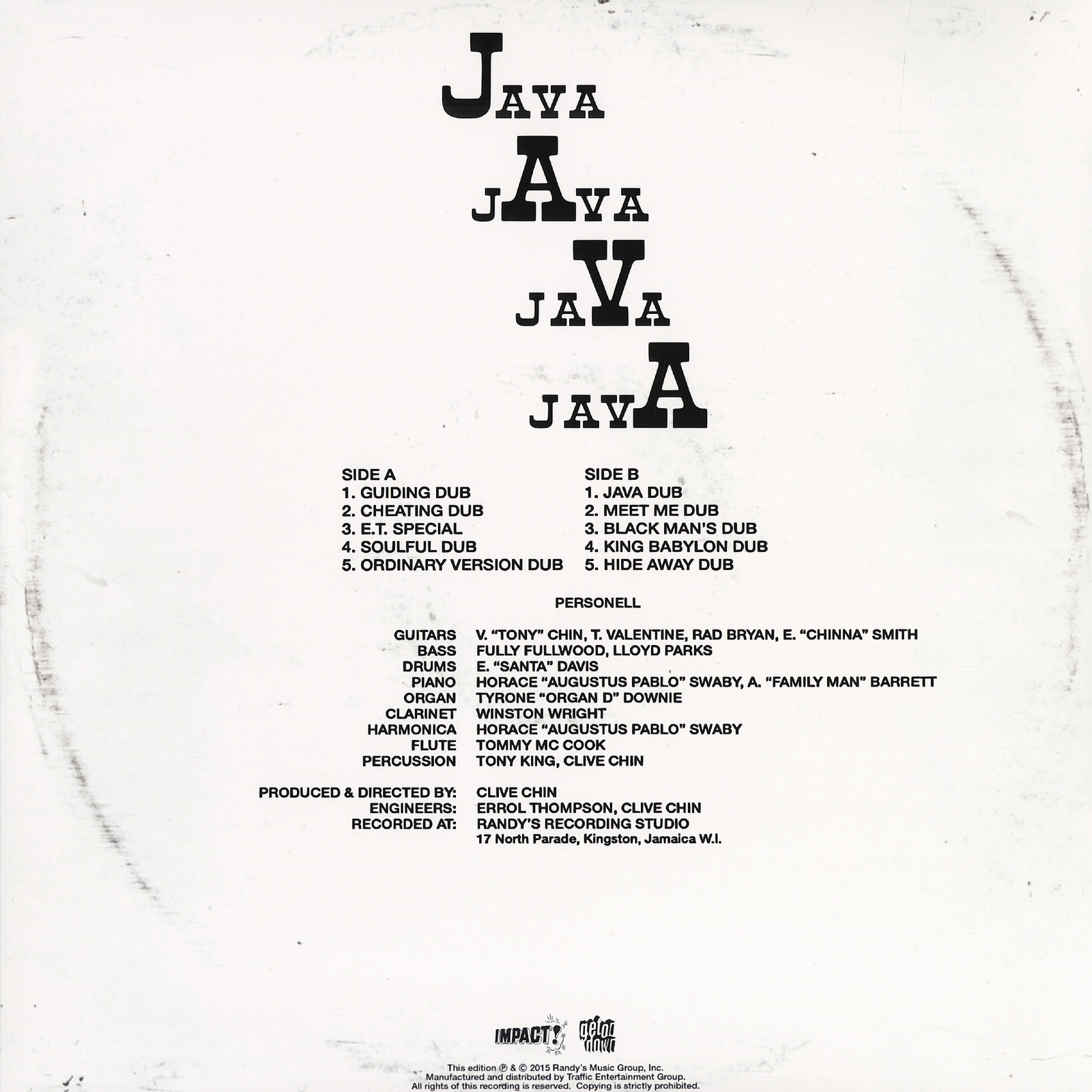

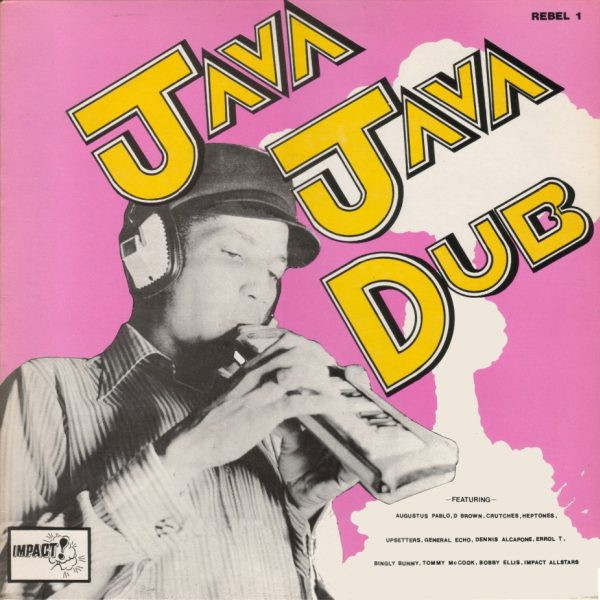

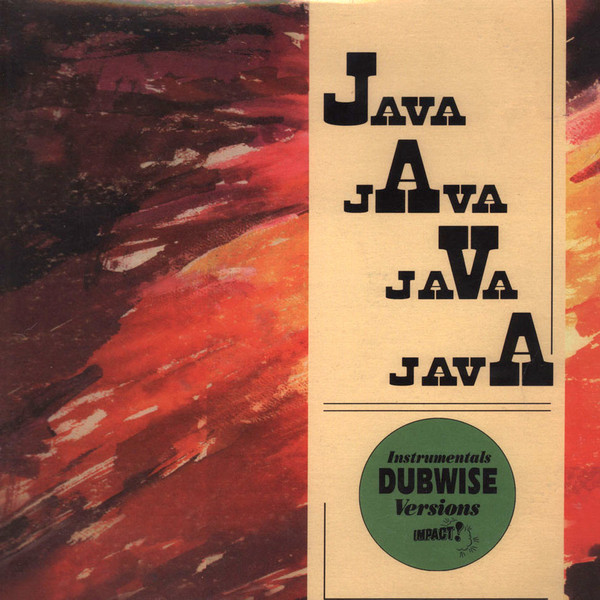

At the center of this sonic revolution sits an album that not many people have ever heard of: Java Java Java Java by the Impact All Stars. Released in 1973 and often cited as one of the very first true dub albums, it remains a foundational piece of music history that deserves far more recognition than its mere 500-copy pressing would suggest.

The Sound System culture that started it all

To understand where dub came from, you need to understand Jamaica’s sound system culture. By the late 1960s, Kingston was alive with massive outdoor parties powered by towering speaker stacks that could shake entire neighborhoods. These weren’t just DJs playing records, these were cultural institutions, with operators like Duke Reid, Coxsone Dodd, and later King Tubby commanding fierce loyalty from their followers.

The sound system operators needed exclusive music to compete with each other, so they’d commission their own dubplate recordings at places like Studio One and Randy’s Studio 17. But here’s where it gets interesting: they also needed instrumental versions of popular songs so their “mic men” could toast over them, talking, chanting, and hyping up the crowd between the bass drops.

These instrumental B-sides, called “versions,” were initially just the tracks with the vocals removed. Simple, functional and designed for a specific purpose. The studio session musicians, many of whom would become legends in their own right, would lay down these backing tracks, often recording multiple songs in a single day to feed the insatiable appetite of the sound systems.

But before 1973, these versions were exactly that: versions. They lacked the wild experimentation, the dramatic manipulation, the sense that the studio itself was alive and participating in the music. Dub wasn’t yet a genre of its own, it was just a tool. The seeds had been planted, but they hadn’t yet broken through the soil.

1973: The year everything changed

If you’re looking for a turning point in Jamaican music history, 1973 is a strong contender. The island’s recording industry had matured considerably over the previous decade. By the early ’70s, Jamaica had a sophisticated network of studios, pressing plants, and distribution channels. Randy’s Records on North Parade in Kingston was one of the epicenters, with Randy’s Studio 17 in the back becoming a factory for hits.

The Jamaican music business was transitioning from ska and rocksteady into the heavier, more hypnotic sound of roots reggae. But the real innovation was happening after the singers went home for the night. Engineers like King Tubby, Errol Thompson, and a young Clive Chin were staying late, experimenting with what happened when you completely re-imagined what a “version” could be.

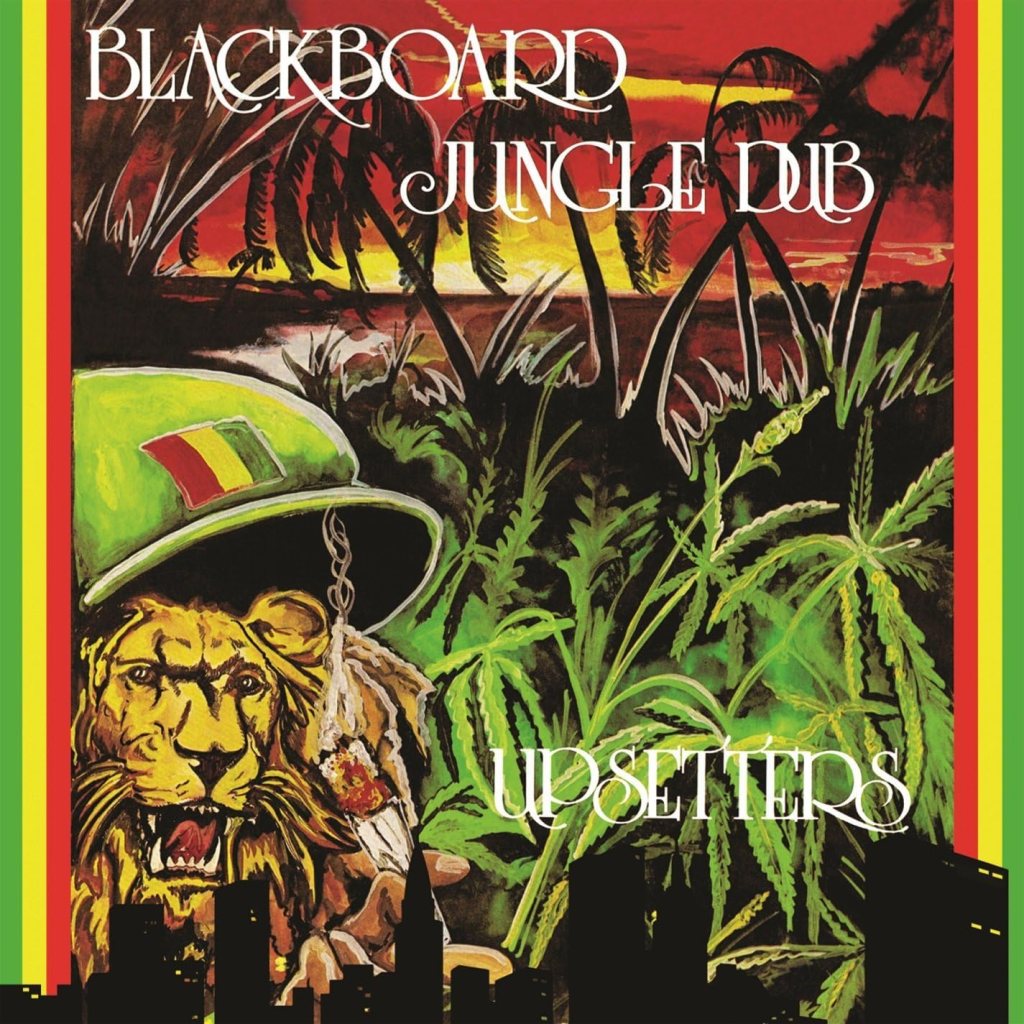

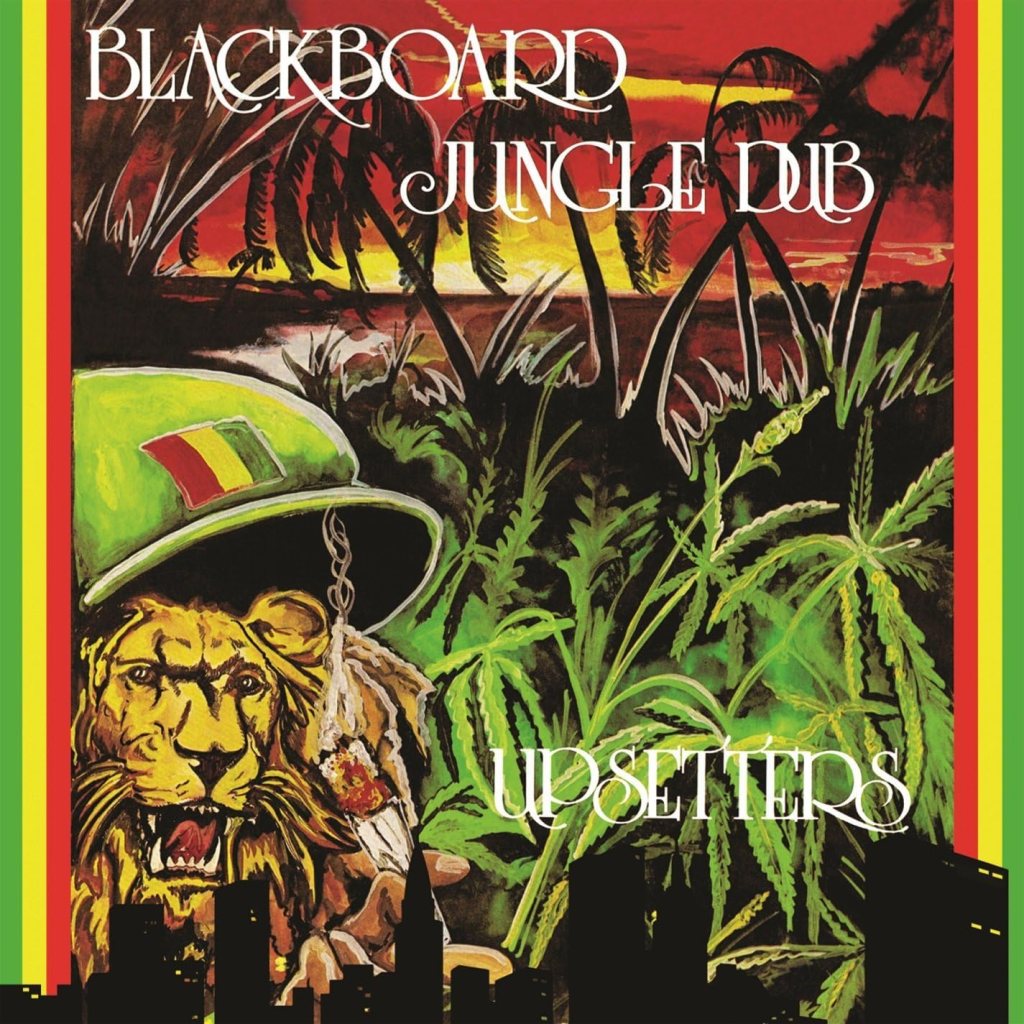

In 1973, several groundbreaking records emerged that helped define dub as its own art form. Lee “Scratch” Perry released Rhythm Shower and Upsetters 14 Dub Blackboard Jungle, both showcasing his increasingly wild production techniques. Herman Chin-Loy dropped Aquarius Dub, and Prince Buster contributed The Message Dubwise. Each of these releases pushed the boundaries of what could be done in the studio.

But among all these groundbreaking works, Java Java Java Java stood apart. While the others were collections of dub versions, transformations of existing vocal tracks, this was something different: a fully realised instrumental dub album, designed from the ground up as an immersive listening experience.

Java Java Java Java: When less became more

Released in 1973 and engineered by Clive Chin and Errol Thompson at Randy’s Studio 17, Java Java Java Java took a different approach than what dub would later become known for. This wasn’t about dramatic dropouts, swirling delays, or psychedelic echo chambers. Instead, Chin and Thompson stripped reggae down to its essential elements and let the raw power of rhythm do the talking.

The album was built on deep, muscular basslines, punchy drums that hit you in the chest, and subtle reverb that created space without overwhelming the groove. It was minimalist, but not sparse, every element had room to breathe, and the restraint was intentional. The result was hypnotic, almost meditative, pulling you into a trance through repetition and rhythm rather than studio trickery.

“At the time it came out, there was no other album like it,” Clive Chin would later recall. And he was right. While dub would soon become associated with King Tubby’s echo drenched productions and Lee Perry’s cosmic experiments, Java Java Java Java represented something purer: the blueprint before the blueprint got complicated.

This was instrumental music designed to stand alone, not just to support a Selecta’s toast. It demanded to be listened to, not just used. And in that sense, it was revolutionary.

The Musicians Who Made It Happen

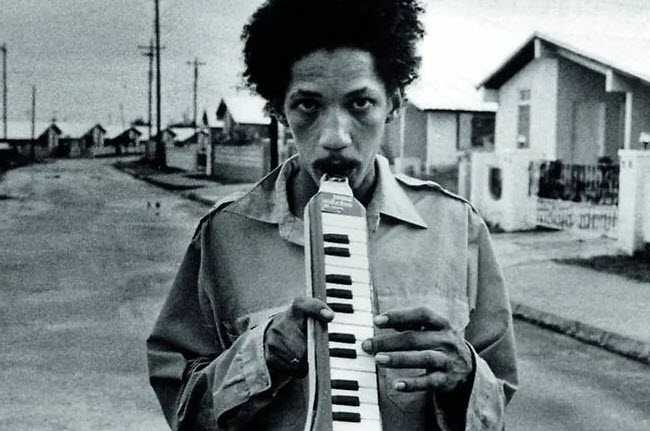

The album’s power came from the musicians behind it: the Impact All Stars, Randy’s Studio 17’s legendary house band. This wasn’t a thrown together session group, these were some of the most talented players in Jamaica, musicians who’d already made their mark on countless ska, rocksteady, and reggae recordings.

Augustus Pablo brought his signature melodica sound, that reedy, haunting tone that could convey both melancholy and hope in a single phrase. Tommy McCook, a veteran of the Skatalites, laid down soulful saxophone lines. Earl “Chinna” Smith’s guitar work provided both rhythm and texture, while Fully Fullwood’s bass anchored everything with earth shaking authority. Winston Wright’s organ added warmth and depth, filling the spaces between the beats.

These musicians had played together so many times that they didn’t need to overthink it. Their chemistry was intuitive, their timing locked in from countless hours in Randy’s cramped studio. They could deliver tight, precise performances while still leaving room for exploration and improvisation. That balance between discipline and freedom is what makes the album work.

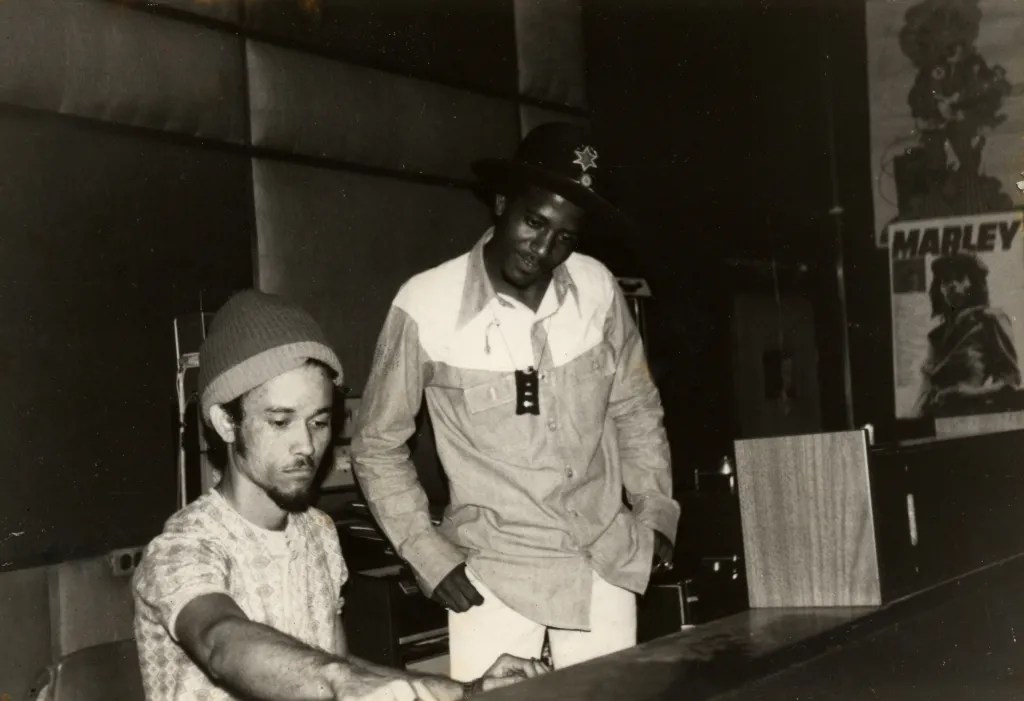

The Masterminds: Clive Chin & Errol Thompson

Clive Chin wasn’t your typical producer. He’d grown up literally inside the Jamaican music industry, his family owned Randy’s Record Store, and by his teenage years, he was already engineering sessions and producing records. His ear was impeccable, and his instincts were ahead of his time.

His first major success came with a single called “Java” by Augustus Pablo, a melodica-driven instrumental that became an international hit and put Randy’s firmly on the map as a powerhouse studio. He followed that with a string of local successes, including Dennis Brown’s “Cheater” and Junior Byles’ “King of Babylon.” By 1973, Chin was only in his early twenties, but he was already a major player in Kingston’s music scene.

Working alongside Errol Thompson, Chin approached Java Java Java Java with a specific vision. While other producers were going wild with effects phasing, flanging, delays bouncing across the stereo field Chin and Thompson took the opposite approach. They created space and depth through rhythmic structure, bass prominence, and subtle engineering touches rather than flashy studio wizardry.

It was a bold choice, and it worked. The album feels both timeless and of its moment, capturing the raw essence of reggae at a pivotal point in its evolution.

The Kingston to Bronx connection

Here’s where the story gets really interesting. While Java Java Java Java was making waves in Kingston, a young Jamaican immigrant named Clive Campbell, better known as DJ Kool Herc, was bringing sound system culture to the South Bronx.

Herc understood something that most American DJs didn’t: the power of the instrumental break. He’d grown up around Kingston’s sound systems, where toasting over versions was the standard. When he started throwing block parties in the Bronx in the early 1970s, he brought that tradition with him, isolating and extending the percussion breaks in funk and soul records so that b-boys could dance and MCs could rhyme.

Herc may not have actually spun Java Java Java Java at his parties his sets leaned more toward James Brown and the Incredible Bongo Band. But the techniques and cultural practices that this album represents were absolutely central to his musical approach. The stripped down instrumentals, the rhythm forward production, the idea that a version could be as important as the vocal track, these concepts, refined in studios like Randy’s, became the blueprint for the early block party sounds that would evolve into hip-hop.

It’s a direct line from the sound systems of Kingston to the parks of the Bronx, and albums like Java Java Java Java are the missing link that often gets overlooked in hip-hop’s origin story.

A rare artifact

Only 500 copies of Java Java Java Java were originally pressed, making it one of the holy grails of dub collecting. In the vinyl obsessed world of reggae and dub enthusiasts, original pressings can command serious money when they occasionally surface.

But the album’s impact far exceeded its limited release. It became a cornerstone of dub’s development, studied and sampled by producers across the globe. From the Bristol sound of Massive Attack and Portishead to the digital dub experiments of Mad Professor and Adrian Sherwood, the influence of this album echoes through decades of music.

It’s proof that you don’t need mass distribution to create lasting cultural impact sometimes 500 copies in the right hands is all it takes.

Why it still matters

Java Java Java Java is more than just a reggae record or even a dub record. It’s a historical artifact that captures a moment of transition and innovation a snapshot of a genre finding its voice, right before it would explode into a thousand different directions.

From its minimalist grooves to its understated production style, the album speaks to the origins of dub as a raw, rhythm driven art form. This was the birth of a sound that would ripple through genres and generations, influencing everything from post-punk to electronic dance music to modern hip-hop production.

Whether you’re deep into dub, curious about reggae’s evolution, or exploring hip-hop’s Jamaican roots, this album is essential listening. Its echoes continue to shape music today, even if most people have never heard of it.

Hear it for yourself

Interested in experiencing this piece of music history? I’ve included some links below where you can grab a reissue copy for your own collection.

[Buy Java Java Java Java – Reissue]

And while you’re at it, I highly recommend picking up Blackboard Jungle by the Upsetters, in my eyes, it’s a must-have dub album for anyone who’s a fan of classic dub reggae.

[Buy Blackboard Jungle – Reissue]

If you do end up grabbing a copy, I’d genuinely love to hear what you think. Drop a comment below with your thoughts on the album or this post, feedback is always appreciated, and I’m always down to talk about music history with fellow enthusiasts.

Leave a comment