When Britain was burning

December 1979. Margaret Thatcher had been in power for seven months, and Britain was already unrecognisable. The “Iron Lady” wasn’t wasting time, she was systematically dismantling the social contract that had held the country together since World War II.

Unemployment was climbing toward three million. The coal mines were marked for closure. Council housing was being sold off. The unions, those bastions of working-class power, were being legislated into irrelevance.

In the streets, the National Front was marching. Brixton, Toxteth, and Southall were powder kegs of racial tension. The police, emboldened by new powers, were cracking skulls in working-class neighborhoods. And hovering over everything was the Cold War dread, the very real fear that Reagan and Brezhnev might turn the whole world into radioactive ash before the decade was out.

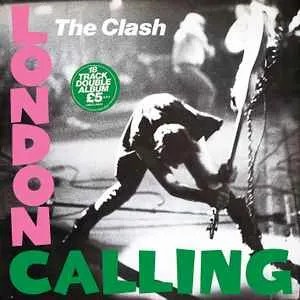

Into this chaos, The Clash released London Calling.

The album’s title track opens with one of the most ominous guitar riffs in rock history, and then Joe Strummer’s voice cuts through like an air raid siren: a desperate transmission from a sinking ship.

The song was inspired by fears of nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island, but it could have been about anything, the Thames flooding, the economy collapsing, society tearing itself apart. Strummer sounds genuinely desperate, like he’s broadcasting warnings from the end of the world. It wasn’t subtle, but it was visceral and real, because Britain genuinely felt like it was crumbling and “I live by the river!”.

This is the context that birthed one of the most important albums ever recorded. London Calling wasn’t just a musical statement. It was a document of social collapse, a working-class howl of rage and resistance, and somehow, improbably, a blueprint for how music could respond to political catastrophe without losing its soul or its groove.

Why everything sounds different: The politics of genre

Here’s what made The Clash dangerous, and what punk purists couldn’t understand: the musical eclecticism of London Calling wasn’t some art-school affectation or a bid for mainstream acceptance. It was a direct reflection of the multicultural, working-class London they came from, a city where Caribbean immigrants, Irish laborers, and white working-class kids were living side by side, sharing music, sharing struggles, sharing a common enemy in a government that wanted them all gone or quiet.

“Jimmy Jazz” bounces with a jazz-influenced groove that would’ve gotten most punk bands laughed out of the room. “Spanish Bombs” weaves together Spanish Civil War history with contemporary Basque terrorism over a rockabilly shuffle, drawing direct lines between the fascism of Franco and the authoritarianism creeping back into Europe. “Rudie Can’t Fail” is pure ska and reggae celebration, a tribute to the Jamaican rude boy culture that had become inseparable from British punk.

And then there’s “The Guns of Brixton,” Paul Simonon’s bass-driven masterpiece that channels deep reggae roots while telling stories of South London tension between Black youth and police.

This wasn’t cultural tourism. Simonon grew up in Brixton. He lived through “the sus laws” that let cops stop and search anyone who looked “suspicious”, which meant young Black men, mostly. The song was prophecy: less than two years later, Brixton would explode in riots that burned for days.

This wasn’t a punk band dabbling in other genres to seem sophisticated. This was The Clash demonstrating that punk’s real ethos, questioning authority, challenging conventions, speaking truth to power, could work in any musical framework. They recorded everything from the New Orleans R&B strut of “Brand New Cadillac” (a Vince Taylor cover that rips harder than the original) to the lounge-jazz cocktail vibes of “The Card Cheat,” which uses its noir styling to tell a story about addiction, desperation, and the violence lurking beneath civilised society.

The genre-hopping was the point. Thatcher’s Britain wanted everyone in their boxes: white here, black there, working class in their place, immigrants somewhere else entirely. The Clash’s musical promiscuity was a middle finger to all of that. It said: we’re all in this together, we’re taking what we need from wherever we find it, and we’re building something new from the wreckage.

The Atlantic divide: when Punk met Punk

By late 1979, The Clash were preparing for their breakthrough US tour, but they were walking into a minefield of expectations and misunderstandings. American punk and British punk had evolved into fundamentally different animals, shaped by radically different political and social contexts.

US punk, at least the version coming out of CBGB and the LA hardcore scene, was often nihilistic, apolitical, or focused on personal alienation. The Ramones were writing three-chord songs about sniffing glue and wanting to be sedated. The Dead Kennedys were political, sure, but in a satirical, provocative way that kept its distance from actual organising. American punk was about opting out, about rejecting the system by refusing to participate.

British punk was different from the start because it had to be. When you’re living in council estates that are literally falling apart, when your dad lost his factory job and there’s nothing coming to replace it, when the police are kicking in your door for no reason, you can’t afford to be nihilistic. You can’t just opt out. British punk, especially The Clash’s version, was about fighting back. It was connected to labor movements, anti-racist organising, Rock Against Racism concerts. It was protest music in a very literal sense.

So when The Clash hit American stages in 1979 and 1980, playing venues like the Palladium in New York, audiences didn’t quite know what to make of them. Here was a band that looked punk, ripped clothes, aggressive energy, Strummer’s manic stage presence, but sounded like nothing else in the scene. They’d launch from a scorching punk anthem into a reggae groove, then into a Motown-influenced soul number, then back to raw rock and roll. And Strummer would be shouting about Thatcher, unemployment, imperialism, political content that felt urgent and specific rather than vaguely rebellious.

Some American punk purists were confused or dismissive. This wasn’t punk as they understood it. Where was the rigid adherence to the three-chord template? Why were they using pianos and horns? Why did they seem to care so much about electoral politics and economic policy? But others, musicians and fans who were looking for something more than just noise and attitude, recognised that The Clash were showing punk’s true potential. They were proving that punk’s anti-authoritarian spirit didn’t have to be sonically restrictive or politically shallow.

The American tour was where “Train in Vain” broke them commercially in the US. The song, allegedly added to London Calling at the last minute, which is why it’s not listed on the original sleeve, had a Motown-influenced pop-soul groove that still sounds fresh today. It became their biggest US hit, and suddenly The Clash were playing arenas. Some accused them of selling out. But here’s the thing: nothing about their politics had softened. They were just proving you could reach millions of people without dumbing down the message.

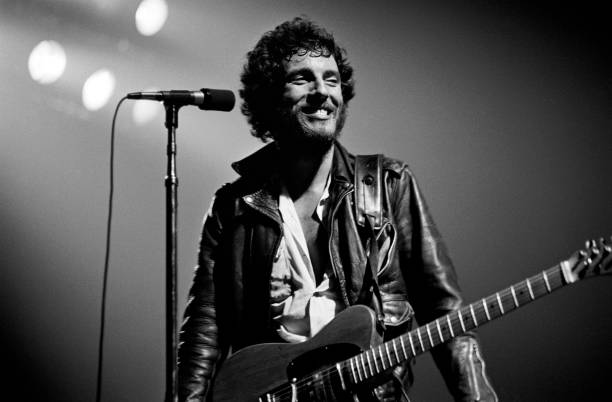

Bruce Springsteen, not exactly a punk guy, called The Clash “the greatest rock and roll band in the world” around this era. He understood what they were doing: making politically conscious music that didn’t sacrifice musicality or accessibility. The Boss recognised kindred spirits, working-class storytellers who refused to choose between artistic integrity and commercial success.

Raw sound, big ambitions

Producer Guy Stevens, known for his chaotic, energetic production style with bands like Mott the Hoople, helped capture something raw and immediate. There are legendary stories of Stevens throwing chairs around Wessex Sound Studios and smashing ladders to get the right energy from the band. You can hear it throughout the album, nothing is too polished, nothing feels safe. Mick Jones’ guitar sounds loose and dangerous, Topper Headon’s drumming is powerful but swinging, and Strummer’s voice is perpetually on the edge of falling apart in the best possible way.

But here’s the crucial thing: it’s not sloppy. For all the chaos of the recording sessions, there’s real craft underneath. Songs like “Lost in the Supermarket”, a surprisingly poignant critique of consumer culture and suburban alienation, show genuine melodic sophistication. It’s a punk band writing pop songs without losing their edge. The lyrics, allegedly about Jones’ childhood but sung by Strummer, capture something essential about Thatcher’s Britain: the hollowness of consumerism as a substitute for community, the way capitalism promises fulfillment through purchasing while destroying the social bonds that actually make life meaningful.

“Clampdown” is the album’s most explicitly political track, a furious indictment of how the powerful maintain control, through propaganda, through dividing the working class, through making people complicit in their own oppression. The line “let fury have the hour, anger can be power / if you know that you can use it” became a rallying cry. This wasn’t abstract protest, this was a tactical manual.

The production captures a band that sounds huge despite limited resources. They recorded the whole thing relatively cheaply, and CBS famously priced the double album as a single LP in the UK—£5 instead of the usual £10, because The Clash insisted on it. Even in their commercial decisions, they were thinking about their audience: working-class kids who couldn’t afford expensive records.

The reception: From skepticism to reverence

When London Calling first dropped in December 1979, the response within punk circles was mixed. Some purists accused The Clash of betraying punk’s stripped-down ethos. How dare they use horns? Piano? Actual musical chops? The reggae and ska influences were acceptable, those had been part of British punk from the start, but jazz? Lounge music? This was apostasy to people who thought punk should sound like the Sex Pistols forever.

But critics immediately recognised something special was happening. Rolling Stone gave it five stars. The NME praised its ambition. Robert Christgau called it the best rock album of the year. More importantly, audiences connected with it, the album went to number 9 in the UK charts despite its experimental nature and eventually sold millions worldwide.

The iconic cover, Paul Simonon smashing his bass on stage at the Palladium in New York, photographed by Pennie Smith in a direct homage to Elvis Presley’s debut album, became one of the most recognisable images in rock history. It captured the album’s essence perfectly: respecting rock and roll history while simultaneously destroying it to build something new. Honoring the past while refusing to be limited by it.

2025: Where is our London Calling?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we’re living through our own version of what Britain faced in 1979, and we don’t have a band like The Clash to soundtrack it.

Look around. The wealth gap between the haves and have-nots is wider than it’s been since the Gilded Age. Working-class communities are being hollowed out by automation, outsourcing, and the gig economy, the 2020s version of Thatcher’s mine closures and factory shutdowns. Millions of people are one medical emergency away from bankruptcy, working multiple jobs just to afford rent, watching their kids inherit a world of debt and diminishing prospects.

We’ve got wars overseas, endless, murky conflicts that drain resources and lives while the public grows numb to the body counts. We’ve got rising authoritarianism, with strongman politics making a comeback across the democratic world. We’ve got scapegoating of immigrants and minorities, the same playbook Thatcher used with her “swamping” rhetoric about immigration.

We’ve got police violence and mass incarceration. We’ve got environmental catastrophe looming, which makes the nuclear fears of 1979 look quaint, at least nuclear war would be quick.

And what’s the soundtrack to all this? Where’s the music that’s capturing the rage, the fear, the desperation, the refusal to go quietly? Where’s the band that’s breaking rules and pissing off purists while speaking directly to young people about the systems that are crushing them?

Mainstream music has largely retreated into either escapism or carefully managed, commercially safe “activism.” We get corporate-approved protest at award shows, Instagram infographics set to trap beats, and artists who’ll wear political slogans on stage but won’t actually risk anything that might affect their streaming numbers or brand partnerships.

Even in punk and alternative scenes, there’s a tendency toward nostalgia, toward recreating the sounds of past rebellions rather than forging new ones, sure we have bands like Bob Vylan, Sleaford Mods and Kneecap who offer their own version of rebellious political commentary, and hats off to them for staying true to cause, but in my opinoin (and you don’t have to agree) , it’s still just about selling albums and concert tickets to a small dedicated fan base who can barely afford to pay their grocery bills.

And before you get mad, I am a fan of all three of these bands and I’m well aware of the impact they have in raising awareness for their causes, but I’m not convinced they have had the same impact on uniting the nations youth as a whole the way the Clash did.

This isn’t a condemnation of individual artists, the music industry has become so consolidated, so algorithmically optimised, so dependent on corporate sponsorship and playlist placement that it’s nearly impossible for genuinely threatening music to break through. The Clash could get London Calling into the Top 10 because the music industry still had room for weirdness, for risk, for bands that might start riots. Today’s industry is designed to prevent exactly that kind of disruption.

What we need: A new subculture, a new sound

The Clash proved something essential: that revolutionary music doesn’t have to be sonically conservative. In fact, it shouldn’t be. The next great protest movement, the next youth rebellion worth a damn, will have to sound like nothing we’ve heard before, just like London Calling sounded like nothing that came before it.

What might that look like? It’s impossible to predict, by definition, it has to come from places and voices we’re not expecting. But we can identify what it would need to be:

Musically fearless. The Clash mixed punk with reggae, ska, jazz, rockabilly, and soul because that reflected the world they lived in. The 2025 version would need to be equally promiscuous, pulling from the full spectrum of contemporary music, hip-hop, electronic music, global sounds, whatever speaks to the moment. Genre boundaries are even more artificial now than they were in 1979.

Politically specific. Vague anger isn’t enough. The Clash named names and addressed specific policies. The next protest music needs to do the same, talk about healthcare, housing costs, student debt, climate policy, surveillance capitalism, all of it. Make the connections explicit between personal struggle and systemic failure.

Working-class and intersectional. The Clash understood that working-class solidarity meant standing with immigrants, with people of color, with everyone getting crushed by the same systems. The new punk needs to build coalitions, not walls.

Willing to be uncomfortable. The Clash pissed people off constantly, punk purists, the music industry, the government, even their own fans sometimes. Comfort is the enemy of change. The next movement needs to be willing to alienate people, to break rules, to prioritize truth over likability.

Actually dangerous. Not dangerous in a performative, shocking-for-clicks way, but dangerous to power. Music that makes authorities nervous. Music that could actually inspire organising, action, resistance.

Does this sound impossible in 2025’s fragmented, algorithm-driven cultural landscape? Maybe. Probably. But that’s what people would have said in 1977 about a punk band making a commercially successful double album that mixed ska and jazz while calling for working-class revolution.

The conditions are right. The anger is there. The alienation is there. The sense that the system is rigged and breaking is widespread, especially among young people who’ve inherited a world of climate catastrophe, economic precarity, and endless war. What’s missing is the spark, the band or movement or sound that crystallises all that diffuse rage into something coherent and unstoppable.

Why London Calling still matters

Here’s why you need this album in your collection, beyond its historical importance: London Calling is a reminder that art can matter, that music can be more than entertainment or escape. It’s proof that you don’t have to choose between musical excellence and political commitment, between experimentation and accessibility, between commercial success and artistic integrity.

It’s nineteen tracks across four vinyl sides, and there’s barely any filler. You can throw it on whether you’re in the mood for righteous anger (“Clampdown”), danceable grooves (“Rudie Can’t Fail”), thoughtful balladry (“Lost in the Supermarket”), or straight-up rock and roll chaos (“Brand New Cadillac”), because it delivers all of that.

The album sounds huge. It tackles apocalyptic fears, police brutality, drug addiction, consumerism, war, love, and personal identity, but never feels heavy-handed because the music is too damn exciting to feel like homework. That’s the genius of it. The Clash made you want to dance and think and rage all at once.

If you’re building a vinyl collection, this is absolutely essential. Look for an original UK pressing if you can, the double album priced as a single LP was a radical statement at the time, but honestly, any pressing will do. This is music that demands to be experienced in full, with the crackle of vinyl adding to its raw, urgent energy.

The Clash proved that punk didn’t have to be narrow-minded or limited. They showed that you could honor your roots while reaching forward, that you could experiment wildly while staying authentic, and that “selling out” wasn’t about musical evolution, it was about losing your principles. London Calling never lost those principles.

Forty-five years later, in a world that feels just as precarious and unjust as the one that birthed this album, London Calling still sounds like a warning and a promise. A warning that things can fall apart. A promise that people will fight back.

We’re waiting for the next band brave enough and talented enough to issue that same warning, to make that same promise, for our moment.

Until then, we’ve got this.

What albums do you turn to when the world feels like it’s falling apart? What music today comes close to capturing this kind of urgency? Or do you completely disagree with everything I’ve talked about ? Drop your thoughts below, I’d love to hear from you.

Leave a comment