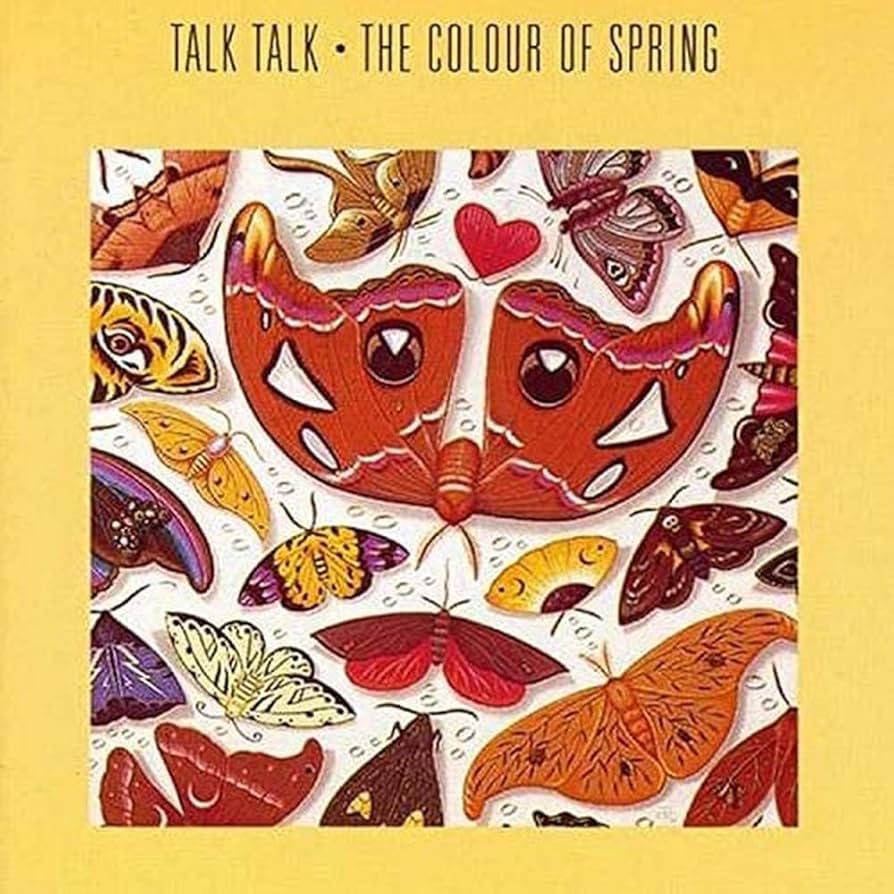

In my recent post about Talk Talk’s The Colour of Spring, (for those of you who didn’t read it you can see it here), I dropped a throwaway line about bands peaking at album three. A few of you called me out and demanded receipts. So here we are.

Fair warning: this theory will piss off at least half of you. It’s based entirely on my own collection and exactly zero scientific research. But hear me out.

I call it Goldilocks Album Syndrome, and once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

The Evidence

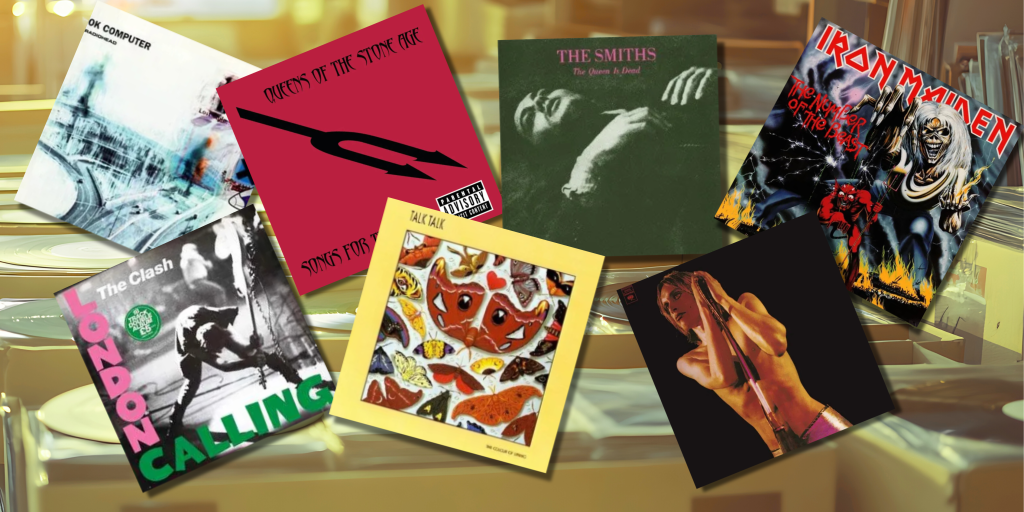

Here’s what’s sitting on my shelf, all third albums, all career-defining:

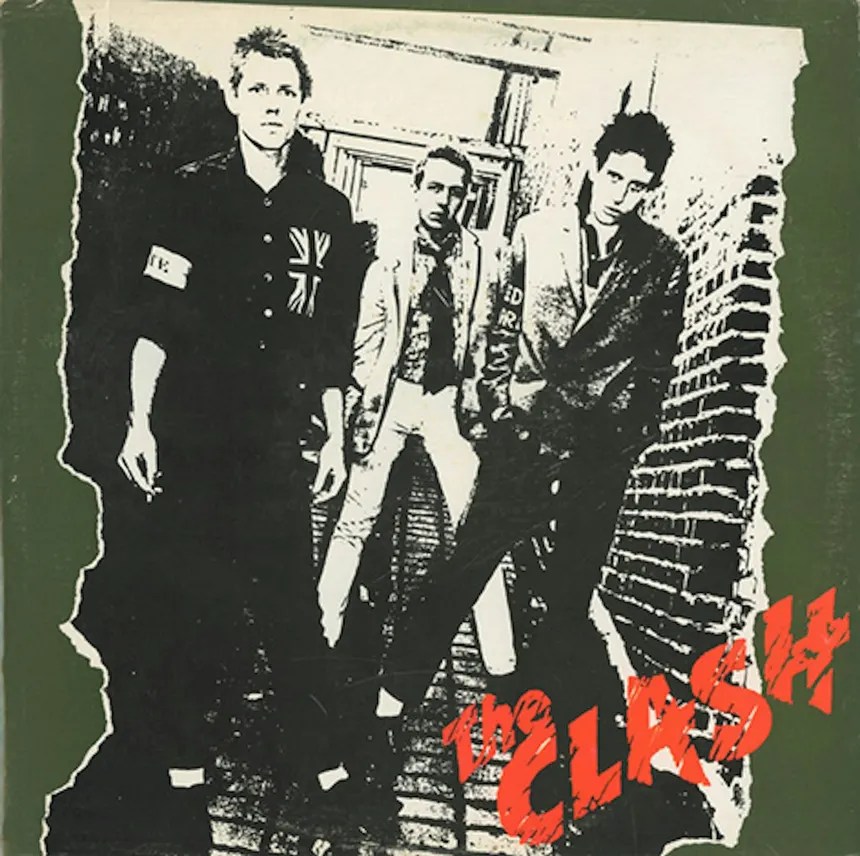

- The Clash – London Calling (1979)

- The Stooges – Raw Power (1973)

- Iron Maiden – The Number of the Beast (1982)

- Talk Talk – The Colour of Spring (1986)

- Radiohead – OK Computer (1997)

- Queens of the Stone Age – Songs for the Deaf (2002)

- The Smiths – The Queen Is Dead (1986)

Every single one is considered a landmark. Coincidence? Maybe. But after obsessively staring at my record shelves (my wife’s words, not mine), I started seeing a pattern.

The Three Stage Journey

Album One: The hunger years

Debut albums are raw, desperate, and often recorded on budgets that wouldn’t cover a weekend at Coachella these days. Bands are squeezing into studios during off-peak hours, or worse, recording in someone’s garage with gear held together by gaffer tape and hope.

The Clash’s self-titled debut? Ferocious, yes. But thin production, rushed sessions, and songs they’d been playing in half-empty pubs for years. The Stooges’ first album? Same deal, pure hunger captured before the studio clock ran out.

Debut albums have fire, but rarely the resources to fully realise the vision.

Album Two: The difficult second album

By album two, things change. The band’s toured, learned how studios work, and maybe scored a minor hit. But now there’s pressure.

Everyone’s watching to see if they can repeat the trick. Worse, they’ve burned through years of material and need to write fresh songs on deadline, usually while touring their arses off.

Some nail it (Nevermind, Led Zeppelin II). Others stumble (Dire Straits’ Communiqué, sorry, but you know I’m right). Album two is often good, sometimes great, but there’s tension. The band’s still learning who they are as recording artists, not just a live act.

Album Three: The Goldilocks Zone

This is where magic happens.

By album three, bands have figured studios out. They know which producers get their vision and which ones are chasing radio hits. They’ve toured enough to understand what connects. They’ve written enough to find their voice.

But, crucially, they haven’t been consumed by the machine yet.

Take London Calling. By 1979, The Clash had resources for a proper double album and confidence to experiment with reggae, ska, rockabilly, whatever. But they still had punk urgency. They hadn’t become the bloated stadium act of Combat Rock (sorry).

Or OK Computer. Radiohead had budget, the right producer (Nigel Godrich), and lessons learned from The Bends. But they weren’t yet the prog-art project of Kid A. One foot in accessibility, one reaching for ambition. Perfect balance.

The industry factor (why this is really about economics, not magic)

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: this pattern is heavily weighted toward 1970-2000. That’s not coincidence, it’s economics.

Back then, you needed labels. No laptop recording. No Bandcamp. No Streaming. You needed expensive studio time, physical distribution (vinyl/CD pressing), and radio play (promotion budgets, pluggers, the works).

The three-album pattern mirrors how labels operated:

- Album 1: Sign band on potential, modest budget

- Album 2: If promising, invest more

- Album 3: Open the chequebook, but not enough to let them disappear up their own artistic arsehole

After album three? Complications. Labels want commercial material, longer tours, faster turnarounds. Bands are exhausted. Creative tensions emerge. The hunger that drove albums 1-3 gets replaced by obligation and mortgage payments.

Why This Matters for Collectors

Even if you think this theory is bollocks, here’s why the “third album rule” works when crate-digging:

Production Quality

Third albums hit the sweet spot, proper resources without over-production. Songs for the Deaf sounds massive but not processed to death. (Side note: I was gutted when Kyuss split, but Homme’s QOTSA rebirth healed that wound fast. That whole Palm Desert scene, chef’s kiss.)

Creative Peak

Bands are firing on all cylinders. Voice found, plenty left to say.

I remember standing in my local record store as a nerdy teen, hearing The Number of the Beast for the first time, Bruce Dickinson weaving theatrical storylines through sonically brilliant tracks. (Yes, technically Bruce’s first album after replacing Paul Di’Anno, but let’s ignore that to maintain my theory, shall we?)

Value for Money

Third albums are often cheaper than debuts in used bins. Everyone wants the debut for cool factor, but album three’s just as good at half the price.

Where this theory falls apart (and why I don’t care)

Before you destroy me in the comments, let me acknowledge the holes:

Debut Masterpieces

Some bands struck gold immediately: The Velvet Underground & Nico, Is This It or Rage Against the Machine, Self titled. These are untouchable debuts.

My theory doesn’t account for fully-formed arrivals. And honestly? I’m not even a Velvet Underground fan. After reading Lou Reed’s biography, he sounded like a complete Twat who couldn’t play guitar to save himself. Yeah, I said it. Heroin chic aside, the emperor had no clothes. (You know the saying: those who can, do; those who can’t, criticise. You’ve probably already decided which category I’m in?)

Late Bloomers

Bowie didn’t hit his stride until… Hunky Dory (album 4)? Ziggy Stardust (album 5)? Good luck picking. And Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours was album eleven! They weren’t ones to give up.

The Never-Peaked Bands

Some bands stayed brilliant forever. Which Fall album is best when they released 400 of them? And Bowie? That man reinvented himself every other Tuesday.

Genre Matters

This works better for rock than hip-hop, where debuts define careers (Illmatic, Ready to Die, Enter the Wu-Tang) all brilliant! Jazz operates on a different level entirely and as for Electronic music? Well it doesn’t even work in album cycles and to be fair it’s not really your conventional “band” setup anyway. As a former 90s Dj try hard, it was mainly about chasing labels and club classic tracks rather than whole albums.

So What’s the Point?

I haven’t discovered a universal music law. I’ve observed a pattern specific to an era when industry economics favored third albums as creative sweet spots.

Is it scientific? No. Will your experience differ? Probably. But next time you’re browsing a band’s discography or standing in a record shop, give album three a shot. More often than not, it’s where they show what they’re truly capable of.

It’s a useful framework for understanding why The Colour of Spring balances accessibility and ambition perfectly, why OK Computer captured Radiohead at peak balance, and why London Calling remains the definitive Clash statement.

Your Turn

Right, theory’s on the table. Now you:

- What’s your best counterexample? Which band peaked at album one, seven, or never stopped?

- Got a pattern you’ve noticed? Something similar in your collection?

- Am I off-base? Or is Goldilocks Album Syndrome real?

Rip into me in the comments. I can take it. And if you’ve got an underrated third album, tell me, I’m always hunting my next essential purchase.

Leave a comment